Thorough preparation is an essential feature of Somali-led peace processes. Typically this involves making initial contacts to establish a cessation of hostilities (colaad joojin) and the formation of a preparatory committee to mobilise people and resources and to ensure security. The committee will usually set guidelines on the number, selection and approval of delegates and the procedures for conducting the negotiations.

The preparatory committee will assign other committees to oversee different aspects of the process, including fundraising. The choice of venue is critical for practical, political and symbolic reasons. The hosting community has responsibility for providing security and covering many of the expenses, which are predominantly raised locally.

Respected and authoritative leadership and mediation talks are chaired by a committee of elders (shirguudon), sometimes from neutral clans. Since effective reconciliation is heavily influenced by the quality of the mediation, facilitation and management, it is fundamentally important that the chair is a trusted and respected person who commands moral authority, and is often a senior elder.

Three senior Somali elders from Somaliland, Puntland and south central Somalia, Hajji Abdi Hussein Yusuf, Sultan Said and Malaq Isaaq, talk in this section of the publication about the qualities that elders are expected to possess. They describe the vital role they play in maintaining peace within their own community and in settling disputes with neighbouring clans. Abdurahman ‘Shuke’ also explains (see p. 58) the importance of traditional institutions, based on xeer (customary law), in laying the foundations for reconciliation and the emergence of stable political structures in Somaliland and Puntland.

Inclusiveness is an important principle of Somali-led peace processes, although women and displaced populations are rarely involved in political deliberations for reasons elaborated in the articles on women and on displacement. The numbers of official delegates are agreed in advance according to an established formula, usually based on proportional representation by clan. Delegates speak and negotiate on behalf of their community, to which they are also accountable. Parties that are not directly involved but who could become an obstacle to a settlement also have to be accommodated.

Poetry, religion and ritual are all significant features, helping to facilitate or sanctify an agreement, and therefore the range of actors includes not only traditional and religious leaders, politicians, military officers, diaspora, business people and civic activists, but also poets, ‘opinion makers’ and representatives of the media – all with recognised roles to play.

Meetings typically attract a large unofficial contingent of people who are part of the constituency to whom delegates can defer and who may contribute through informal mediation, specific expertise, drafting agreements or mobilising support. Often the final stage of a process is witnessed by delegates of neighbouring clans, adding weight to its conclusion. Inclusiveness is just as important in non traditional processes, as illustrated by the account below of the operation of the District Committee in Wajid (see p. 70).

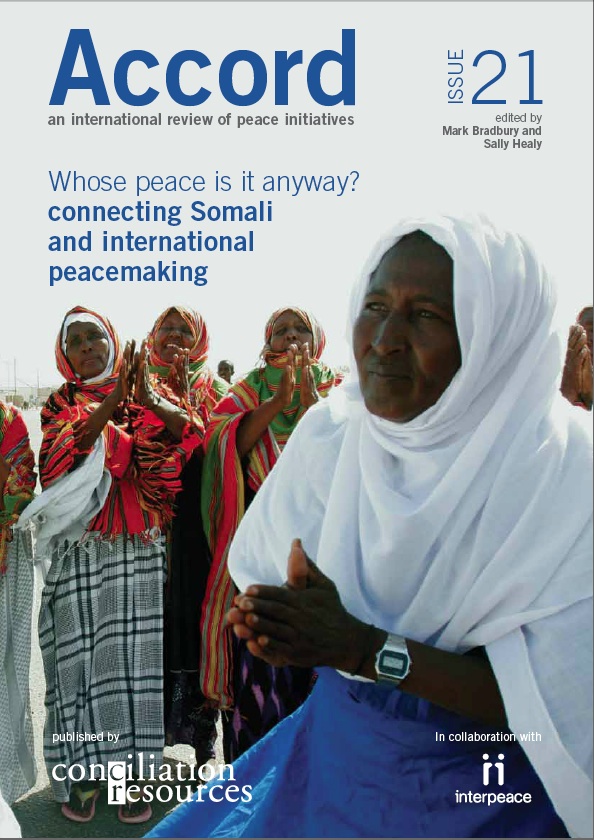

Women’s roles are rarely recognised beyond their support for logistics in traditional inter-clan processes. As Faiza Jama Mohamed explains in her article on women and peacebuilding (see p. 62) , women’s position in society – as daughters of one clan or lineage and often married to another – has denied them a formal role in politics. Nevertheless women have organised themselves using innovative tactics to mobilise support and to pressurise parties to stop fighting and continue dialogue when it appears to be faltering.

In Somaliland peace conferences, women recited poetry to influence proceedings. In 1998 in the Puntland parliament a woman poet shamed male delegates into allocating seats for women. Elsewhere women have pressed elders to reach an accord and avoid conflict by offering to pay outstanding diya (blood compensation).

In many urban settings women have been able to play more influential roles, as Faiza Jama highlights in her account of the remarkable efforts by women civic activists who have ‘waged peace’ in Mogadishu and elsewhere.

Consensus decision making is another key principle of Somali peacemaking. The time needed to negotiate consensus is one reason for the length of some Somali peace processes. Malaq Isaak observes (see p. 50) that speed can kill peace processes. Different forces may be brought to bear to encourage resolution, including the burden of financial costs being borne by the hosting community or lobbying by groups of stakeholders (often women). The authority of peace accords derive from the consensus decision making process as well as the legitimacy of the leadership, the inclusiveness of the process, and the use of xeer. Abdurahman Shuke explains how the use of xeer has been fundamental for the restoration of peace.

Somali negotiators adopt an incremental approach to peacemaking. First attempts to resolve a conflict often fail and a process may be restarted with new strategies and participants learning from one initiative to the next. Many of the larger conferences are the culmination of several smaller, localised meetings.

It is not uncommon for Somali peace processes to spread over many months or even years. The process leading to the conference and implementation of the accords produces the peace, not the conference itself. Hajji Abdi Hussein (see p. 60) explains how Somaliland’s successes in reconciliation and statebuilding in the 1990s are attributed to a sustained focus on resolving issues at a community level before tackling broader governance issues.

Somali-led peace talks typically ensure effective public outreach throughout the process and wide dissemination to ratify the outcomes. This is recognised as critical to the legitimacy and sustainability of peace accords.